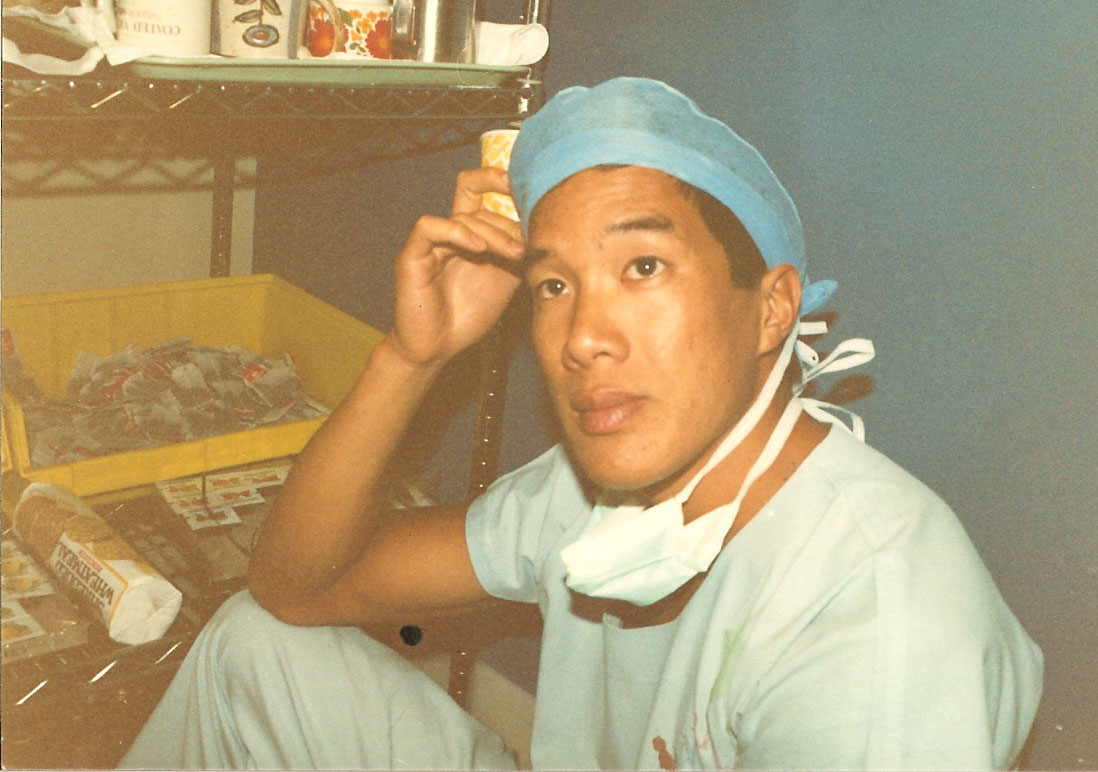

“When it comes to preparing for neurosurgery, I like to see myself as some sort of elite athlete. When you look at those athletes, one thing that really comes across is their amazing focus. This incredible drive to win. That’s what I try to do when preparing for surgery. I tell myself this patient is my loved one. I’m going to treat this patient like they are a member of my own family. What would I do if it was a family member? I’d make sure everything was optimum. I’d make sure my personal state was optimum, the people around me had the same mentality, my team was the best and my equipment was the best. That’s what I do for every patient.

But of course, it hasn’t been an easy road…

Why would one choose neurosurgery? I think it’s one of the most physically and emotionally taxing specialties in the medical field. Patients can die within minutes. You can’t make mistakes. It’s totally unforgiving. There is zero room for error.

I recognised this about neurosurgery as a medical student. When I worked in the emergency room, if a neurosurgery patient would come up, I would get the file and slip it underneath and take the next file. I found it all too burdensome and horrible. My first impression was that I wanted absolutely nothing to do with it. To be quite honest, I feared neurosurgery.

I love kids so in 1984 I started on a career in paediatric surgery. But just as I was finishing my training the neurosurgery registrar fell ill, and they asked me to cover his call schedule. I found myself thrust into the specialty that I absolutely feared the most!

What happened surprised me. When I was forced to understand it, to read about it, to learn about it, my mindset started to shift. It ticked all the boxes of being incredibly challenging and you could still be a pioneer in neurosurgery because so much was still unknown. I didn’t really like the emotional part of it, but you’ve got to take it on the chin. If you want the joy of operating on people and saving lives, you’ve got to learn to carry the burden of people dying.

But there is nothing worse than the death of a child.

Alegra was my patient. She was diagnosed with brain cancer – a type of brainstem glioma – at the tender age of 5.

Brainstem gliomas are terrible tumours. They have been considered inoperable by most neurosurgeons in the world. The brainstem is this structure that is about the size of your thumb, through which all the neurones from the cerebrum travel to the spinal cord. So essentially everything runs through the brainstem. It has within it the areas that control your breathing, pulse rate, swallowing and eye movement. It’s so vital that surgery on the brainstem is considered taboo, out of bounds to even the most skilled of surgeons. Brainstem tumours account for about 10-20% of all the brain cancers we see in children. All I can do for some of these children is to buy them more time.

I operated on Alegra at Christmas time. In the 10 months that followed she was incredibly brave and courageous. She endured surgery with me, 30 radiotherapy treatments, countless MRIs, blood tests and doctors’ appointments. She even started Kindergarten!

Despite the short time I knew her, despite her youth and despite the tragic circumstances under which we met, I will never forget her warmth and the calmness and gratitude that she exhibited. She was an old soul, but at the same time a reminder of the purity and innocence of youth.

Alegra was thoughtful, well-considered and already had big plans for her future. She had a caring nature and wanted to be a teacher. She wanted to marry her boyfriend, Paris, at age 20 and go to Disneyland for their honeymoon. She understood the feeling of true love and always asked others for their love story.

How terrible that the world won’t get to know Alegra beyond her 6 short years on Earth.

Brain cancer is killing more of our kids than any other disease in Australia. And with a fact like this, you’re probably sitting back thinking, ‘if it is killing more children than any other disease, surely it gets the most funding?’

But sadly no, across developed first world countries including Australia, brain cancer is poorly funded compared to some other cancers. It has a significant socio-economic impact on our society as a killer of children and young people, yet governments aren’t pouring in the research funding. Brain cancer isn’t a common cancer, so put simply: it doesn’t win votes. That’s why it was a no brainer to set up the Charlie Teo Foundation. We’re raising the money and funding the research so desperately needed.

I think brain cancer deserves the biggest slice of the funding pie!

It’s not fair that children like Alegra are dying and there are no treatments for them. I don’t want to have to tell another parent, I can’t save your child.

As a society we can’t sit back and allow brain cancer to kill our children any longer.”

References

- Brain cancer kills more children in Australia than any other disease (AIHW 2020).

- Brainstem tumours account for 10-20% of all childhood brain cancers (J NeuroOncol 2017)

- Brain cancer has a high socio-economic impact on society (AIHW 2017), yet receives less funding than some other cancers (AIHW 2021)

- The radical surgical resection of brainstem gliomas can be performed with acceptable risk in well-selected cases and likely confers survival advantage for what is otherwise a rapidly and universally fatal disease (World Neurosurg 2021)